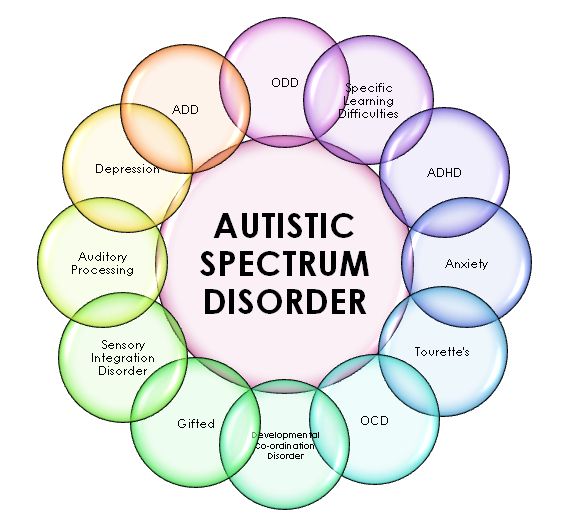

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has become a focal point for ethical discussions in academia, healthcare, and societal frameworks. As we delve into the intricate nuances of autism, we must ask ourselves: Is our current understanding sufficient to cater to the diverse needs of individuals on the spectrum, or are we merely scratching the surface? This inquiry unveils a myriad of concerns that intersect ethics, research, and the lived experiences of those affected by autism.

The diagnosis of autism is notoriously complex, marked by variability in symptoms and responses. To navigate this landscape ethically, it is vital to establish a robust ethics policy. Such policies must not only embody respect for the rights of individuals with autism but also be adaptable to the evolving understanding of the disorder. A poorly conceived ethics policy could exacerbate existing challenges. It might inadvertently propagate stigma or foster isolation, which contradicts the very essence of inclusion we strive to achieve.

One of the primary ethical dimensions of autism revolves around autonomy. The notion of autonomy is predicated on the individual’s right to make personal decisions about their lives, including treatment and educational pathways. How do we respect this autonomy when many individuals with autism may struggle with communication or decision-making capabilities? This conundrum is emblematic of a larger societal challenge: empowering individuals with disabilities while simultaneously ensuring their safety and well-being.

Moreover, informed consent becomes a significant issue when special populations are involved. For instance, what constitutes ‘informed’ when individuals may not fully comprehend the implications of their choices? Researchers and practitioners must navigate these murky waters judiciously, ensuring that consent is genuinely informed and not a mere formality. This leads us to question: Are current frameworks sufficient for obtaining truly informed consent, or do they need recalibration to fit the unique context of autism?

Another pressing ethical consideration is the role of research in enhancing our understanding of autism. While research drives advancements in treatments, therapies, and educational methodologies, the ethical ramifications are profound. The pursuit of knowledge must not come at the expense of the individuals it seeks to benefit. This principle calls for stringent ethical oversight in research protocols involving participants with autism.

For instance, the practice of including only high-functioning individuals in research could skew our understanding of autism. It might lead to generalizations that ignore the experiences of those with more significant challenges. Therefore, a diversified research participant pool is imperative. However, this raises the ethical question: How can researchers engage with individuals who may lack the capacity to provide informed consent?

Furthermore, the development of diagnostic criteria and interventions warrants careful ethical scrutiny. The DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) has made strides in broadening the diagnostic criteria for autism; however, fluctuations within these criteria can also create challenges. Are we at risk of medicalizing behaviors that should be viewed as part of the human condition? The ethical implications of labeling individuals must not be understated. Labels can foster understanding, yet they can also lead to misunderstanding and marginalization.

As we ponder the ethical landscapes surrounding autism, the concept of inclusive education emerges robustly. Ethical policies must advocate for educational environments that genuinely accommodate all learners—regardless of their abilities. This inclusivity is not merely an ethical obligation but also a societal benefit. Valorizing the experiences and perspectives of individuals with autism enriches the educational fabric for everyone. Herein lies another dilemma: how do educators balance the diverse needs of students while adhering to standardized curricula?

Moreover, transitioning to adulthood poses another set of ethical quandaries for individuals with autism. Often, individuals find support systems falter as they age out of educational environments. Ethical policies must, therefore, extend beyond childhood and adolescence, addressing ongoing support in areas such as employment and life skills. Will society rise to the challenge of integrating individuals with autism into the workforce, or will we continue to create barriers that inhibit their professional growth? This inquiry compels us to reconceptualize the role and responsibility of communities in supporting lifelong wellbeing.

In terms of care and support strategies, the ethical implications of behavioral interventions merit attention. Applied behavior analysis (ABA), a commonly utilized approach, sparks debates regarding its ethical ramifications. While it has proven effective for many, questions linger about its applicability to everyone on the spectrum. Are we inadvertently endorsing practices that prioritize compliance over the individual’s self-determination and emotional well-being?

Furthermore, advocacy plays a critical role in shaping future directions related to autism ethics. Advocacy efforts must champion the voices of individuals with autism, ensuring that their perspectives shape policy-making processes. The creation of autism ethics committees within organizations can enhance accountability, fostering environments that prioritize ethical considerations in decision-making. Such committees can serve as platforms for dialog and facilitate the collaboration between individuals with autism, families, advocates, and professionals. How do we ensure that the advocacy landscape remains inclusive and representative of the diverse experiences across the autism spectrum?

As we venture forth into this expansive terrain, it becomes imperative to recognize that our understanding of autism is far from static. Just as the spectrum evolves, so must our ethical policies and practices. The future of autism—and indeed the broader societal understanding of disabilities—will hinge on our capacity for empathy, adaptability, and progressive thought. Ultimately, crafting a nuanced and effective ethics policy is not merely an academic exercise; it is a moral imperative that will shape the experiences and lives of current and future generations.